Indian athletes and social media: it’s complicated

Two recent controversies involving former India cricketers Virender Sehwag and Venkatesh Prasad showed just how tricky the business of social media management for athletes is

Good evening!

Welcome to The Playbook, a weekly newsletter on the business of sports and gaming. If someone shared this newsletter with you or if you’ve found the online version, please hit the subscribe button below — it’s free! You can unsubscribe anytime.

On October 14, 2022, we at The Signal published the first edition of The Playbook, a weekly newsletter that promised to go deep into the business of sports and gaming from India and around the world. That first edition was about how Disney Star was building a moat to quell the charge of its new rival, Viacom18.

What a year it has been, eh? Recent reports suggest Disney has considered selling its India assets to Viacom18, among other parties. It just shows how unpredictable and exciting the world of sports business is. As I sit down to write this edition that will be published on the eve of The Playbook’s one-year anniversary, I want to start by thanking all of you for sticking with me through this ride. I couldn’t have done it without your constant support, engagement, and occasional brickbat!

As we enter year two of The Playbook, I’d love to go a little deeper into what you think about this newsletter. Which is why I’ve created a short reader survey. I’d really appreciate it if you could take out 15 minutes to participate in this survey, which will help me understand what I’m doing right, what I’m doing wrong, and what I can do better.

A big thanks also to all of you who participated in last week’s poll. More than 60% of you think that playing games of skill with stakes amounts to gambling. Here are some of the comments I received (edited for clarity):

Kautilya: “All so-called real-money games are indeed gambling since they involve the three core essentials of gambling: consideration, prize, and chance. You put some money in (consideration), there’s a payout (prize), and there’s the element of chance in the outcome. Yes, some level of skill is indeed involved, but it doesn’t take away these three fundamental elements.”

Rohan: “At the outset, it might not look like gambling, but it is addictive. And if not stopped at the right time, a person might lose all his hard-earned money.”

Keshav: “Any game that includes money (which is bet on the outcome) is gambling. Similar to what happens in cricket betting.”

***

Right, let’s get into today’s edition, which is about social media management of athletes.

A double-edged sword

Photo credit: Virender Sehwag and Venkatesh Prasad on X

In early September, former India cricketers Virender Sehwag and Venkatesh Prasad kicked up a bit of a storm on X (formerly Twitter).

Sehwag urged the Board of Control for Cricket in India (BCCI) to get the Indian cricket team to be called Bharat instead of India. This was around the time a political controversy had erupted in the country over the use of Bharat and India. But Sehwag claimed his reasons weren’t political.

I have always believed a name should be one which instills pride in us.

We are Bhartiyas ,India is a name given by the British & it has been long overdue to get our original name ‘Bharat’ back officially. I urge the @BCCI@JayShah to ensure that this World Cup our players have… twitter.com/i/web/status/1…

Prasad was on a different sort of trip. He started tweeting about the ICC World Cup tickets fiasco (which I’ve written about here). He also attacked the organisers of the Asia Cup for allotting a reserve day only for the India-Pakistan match, calling it “absolute shamelessness”.

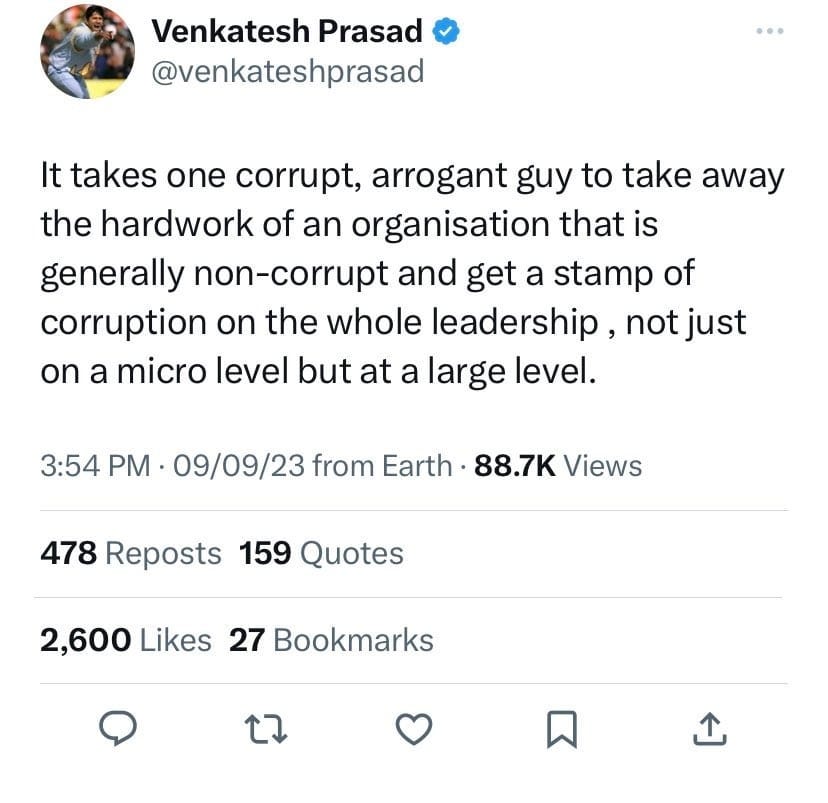

Then, on September 9, Prasad posted this.

The post was deleted within hours, but not before people began speculating whether he was referring to Jay Shah, who heads both the BCCI and the Asian Cricket Council. Then, the following day, Prasad posted an edited version of his tweet.

It takes one corrupt, arrogant guy to take away the hardwork of an otherwise non-corrupt organisation and spoil the reputation of an entire organisation & the impact isn’t just micro but at a macro level. This is true in every field, be it politics,sports, journalistm, corporate.

The polarised nature of social media ensured that Sehwag and Prasad got praise and flak for their posts. Among the brickbats, though, was the fact that they did not sound like themselves in some of the posts and replies. Prasad even went on to attack Mohammed Zubair, the co-founder of fact-checking website Alt News, who had posted screenshots of his deleted tweets and some of the replies speculating whether he was talking about Shah. Prasad called him a “serial hate-monger”, “agenda peddler”, and even seemed to equate him with a terrorist.

It wasn’t long before X users pointed out that both former cricketers had the same social media manager. Some users, including Zubair, even dug out old tweets of the manager that were of a particular political leaning.

It was all rather ugly. And completely avoidable. Prasad’s case was especially bizarre because he did something rather off-script for any Indian cricketer, current or former. He criticised the all-powerful BCCI, headed by the son of India’s home minister. Indian sportspersons, especially cricketers, don’t usually go anti-establishment.

In 2021, when India received global criticism over the farmer protests, several Indian cricketers tweeted saying it was an internal matter and called for unity in the country, with a government-sanctioned hashtag. These included the likes of Sachin Tendulkar, Virat Kohli, and Rohit Sharma.

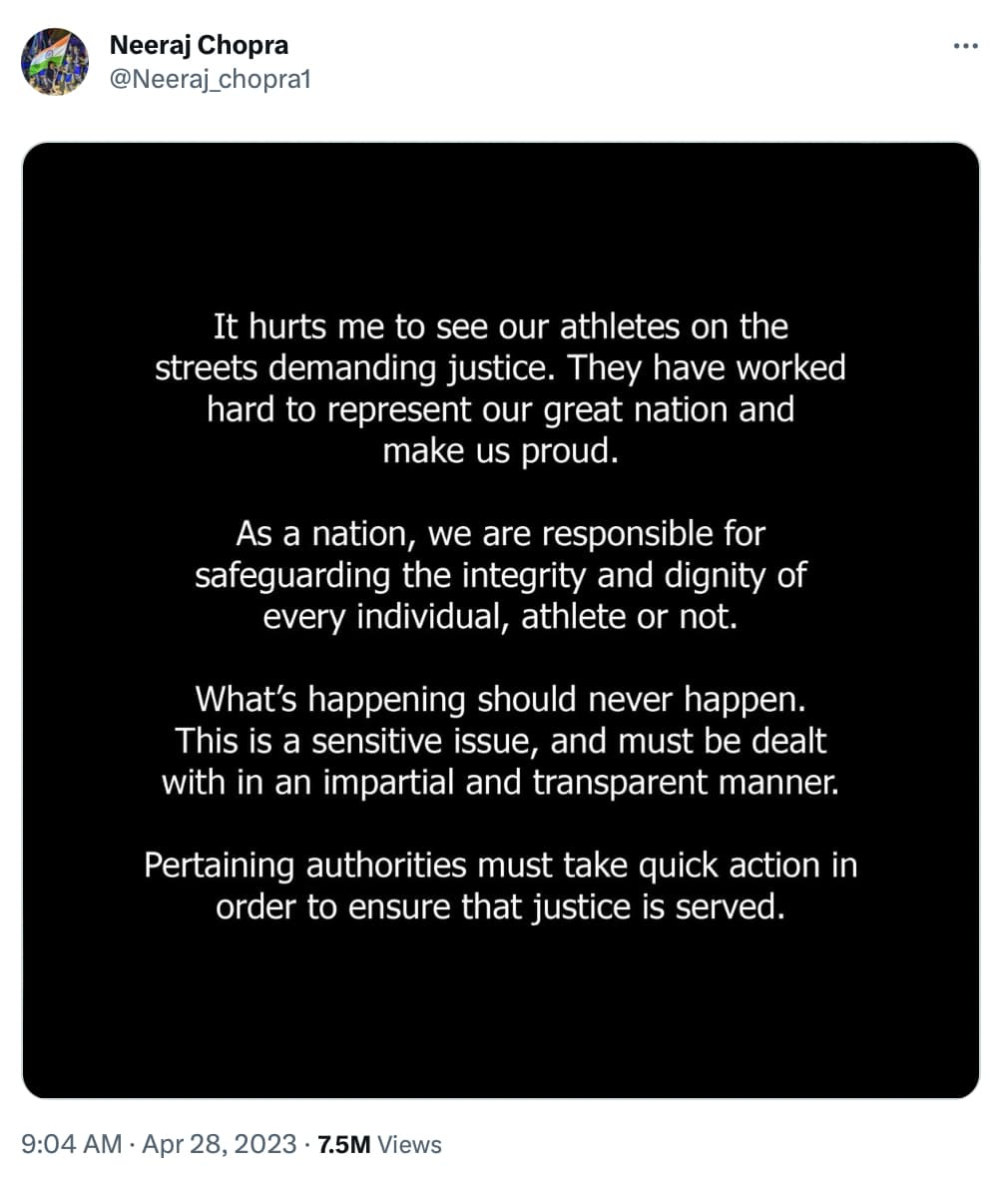

None of those cricketers tweeted anything earlier this year when India’s top wrestlers were manhandled and detained by the police during a protest in Delhi. Only a few Indian sportspersons, including Neeraj Chopra, Sunil Chhetri, Abhinav Bindra, and CK Vineeth, spoke up against the detention.

But just when you thought Prasad was becoming the hero Indian cricket needs, he did a U-turn. And the more he tweeted and attacked his detractors, the more doubtful it became that it was indeed he who was tweeting.

If the Sehwag and Prasad episodes prove anything, it’s that you can’t get away with something that’s not “on brand” on social media. That’s why social media managers spend a lot of time with their athletes to understand them better. “If it’s not authentic to the personality of the athlete, it comes through,” says Sharba Tasneem, Head, Talent & Programmes at sports marketing agency Meraki Sport and Entertainment.

“Our social media managers talk to the athletes on a regular basis. A lot of time goes into gauging how the athlete speaks and how they react to something. A lot of our athletes aren’t proficient in English, so if it’s a well-constructed post in English on social media, followers will know that it’s not the athlete posting.”

Sharba Tasneem, Head, Talent & Programmes, Meraki Sport and Entertainment

That’s one of the reasons Sehwag and Prasad got called out. Once their followers realised it probably wasn’t them tweeting, they would have felt let down. “That’s why trust matters a lot, especially if you’re someone who did not grow up in the world of social media,” says a senior executive at a sports management agency who requested anonymity to protect business relations. “I’m sure Sehwag and Prasad would have known what’s being posted on their accounts, but I don’t think they would have been informed well enough of the consequences.”

With current, active athletes, sports management agencies work closely with them to chalk out a social media strategy. This includes making a content calendar and listing things that the athletes can or should talk about to showcase their personalities, says Divyanshu Singh, chief operating officer at sports management company JSW Sports. “We also try to define their personality: what do I want X athlete to stand up for, what’s the message I want their followers to get, what side of them do I want to show beyond their sport. That’s where strategic thinking comes in.”

To some athletes, like 23-year-old cricketer Jemimah Rodrigues, social media comes naturally to them. “Jemimah does stuff that even inspires me and my social media team,” says Singh. “From jamming with musicians to creating cool Reels, she is very forthcoming, not shy at all, and does so much on her own.”

But Rodrigues is an exception rather than the norm. One of the main challenges for talent management companies is convincing their athletes to post more, with social media being a crucial tool for brand building and monetisation. While cricketers get more exposure in India and are more media savvy, that’s not the case with athletes from other sports.

“Fundamentally, athletes are shy and reserved in nature,” says Singh. “So, we spend a lot of time with them in media training. Their competition is coming from social media influencers in the genres of music, entertainment, fashion, and lifestyle, who have more followers than these athletes. So, it’s very important for them to grow their brand and showcase their personal side.”

Once the content strategy is set, the next step is execution. Athletes’ involvement and interest in their social media activity varies on a case-by-case basis. In general, the degree of involvement is directly proportional to the number of followers the athlete has. Someone like Virat Kohli or Rohit Sharma would like to see everything run by them unless it’s a sponsor commitment, says the senior executive quoted earlier. The more followers you have, the more paranoid you’ll be about what’s going out on your handle. The younger athletes are more likely to trust their agency to do the right thing.

“Sometimes, athletes will send us a picture or video and ask us to post it,” says Meraki’s Tasneem. “We also advise athletes that they should post about a certain topic. And it’s important the athlete is aware of what’s going out from their handles. Tomorrow, if it becomes news, it shouldn’t catch them off guard.”

One of the pitfalls of outsourcing social media to an agency is what happened with former India cricketer Sourav Ganguly last year. While sharing a promotional tweet, the agency handling Ganguly’s social media pasted the entire message from the client, e-commerce platform Meesho, including the instructions: “Please ensure that the Meesho brand name or Meesho hashtag is nowhere mentioned in tomorrow’s 1st September post.” Meesho tried its best to salvage the blunder.

This was, of course, an honest mistake and hardly the first such occurrence worldwide. To avoid such gaffes, Tasneem says Meraki tries to restrict the number of athletes handled by a social media manager to two and also have a separate device for each athlete.

Usually, if an athlete has signed up with a sports/talent management company, it also handles their social media. If there are two different agencies, it increases the chances of the athlete’s social media page looking like a sellout. It’s important for the agency to figure out the right balance between genuine and paid posts. “If your page only has branded content, your engagement is going to start dropping,” says Singh.

Paid posts or collaborations can either be a part of a long-term endorsement contract or standalone influencer marketing campaigns. With top athletes like Kohli, Sharma, and Chopra, agencies try and avoid doing standalone posts because they could end up blocking big-ticket endorsement deals. “With Neeraj, we’ve positioned him as an athlete of a particular stature, and he’s only doing long-term endorsement deals,” says Singh.

However, he also points out that with the advent of influencer marketing, there is now a lot more logic and science in how athlete valuations are done.

“Valuating an athlete has been a very subjective thing because, in India, we’re very hype-driven. If an athlete does well and is shining, their market rate goes up. If they’re not doing well or injured, it goes down. There is no science to it. But with social media, because of the metrics available, we’re able to justify with a lot more conviction why a particular athlete should be paid a certain rate. There are various metrics to gauge whether an athlete is a nano-influencer, micro-influencer, macro-influencer, and so on. Brands also want higher accountability and return on investment. The days when they just go and splurge on a big celebrity are gone.”

Divyanshu Singh, COO, JSW Sports

Of course, the downside to connecting your brand endorsements to your social media accounts is that you need to be a lot more cautious when it comes to taking stands on sensitive or political issues. You might also be forced to put out something you don’t want to. Like during the farmer protests.

“A lot of athletes reluctantly pushed out tweets because they were asked to,” says the senior executive quoted earlier. “It was evident in some of the language of the tweets. But they don’t have much choice when it comes to such things.”

Unless you’re MS Dhoni.

The legendary and enigmatic former India captain, who has 46 million followers on Instagram, does not do any paid posts. His Insta feed only has personal posts about his day-to-day life. And he’s not even a regular poster. “Dhoni can get away with it because that’s how he has built his persona online. No one can get in touch with him. His social media is pretty much controlled by him only. Even if he has a social media manager, they’re probably quite jobless,” adds the senior executive, laughing.

Curiously, though, Dhoni’s Facebook page, where he has 27 million followers, is full of paid posts and no personal ones. But even there, he has managed to avoid posting about the farmer protests or any other political matter.

But if your client isn’t Dhoni, what’s the best way for an agency to deal with political controversies? Tasneem says her team tries to gauge whether the athlete posting about something would benefit society at large. “If it’s something that affects the athlete at a personal level and they are comfortable talking about it, then they get involved. If they aren’t comfortable, they don’t. You shouldn’t jump on the bandwagon because everyone else is doing it. It needs to make sense why you are talking about it.”

JSW Sports’ Singh concurs, saying the only advice they give their athletes is to be themselves. “Sometimes, because of the political fabric, we also get stuck as to what is diplomatically the right thing to do. But we always encourage our athletes to be authentic.”

For instance, during the wrestlers’ protest earlier this year, Chopra wanted to speak out in support of his fellow athletes. “He was very smart about it: he just said athletes should never go through something like this. He did not try to instigate and say what is wrong and what is right. He’s very articulate,” says Singh.

In 2021, Chopra even stood up for his Pakistani counterpart Arshad Nadeem after a controversy erupted over the latter using the Indian’s javelin at an event. Chopra posted a video and message requesting people to “not use me and my comments as a medium to further your vested interests and propaganda.”

That same year, Kohli surprised many by making a strong statement in support of his teammate Mohammed Shami. The Muslim cricketer had received a lot of abuse on social media after Pakistan beat India by 10 wickets in the T20 World Cup. “To me, attacking someone over their religion is the most pathetic thing that a human being can do,” Kohli said.

In both cases, it’s unlikely the athletes would have said what they did because someone told them to do it, says the senior executive quoted earlier. “The default for most social media agencies is to stay away from controversies. Don’t do anything that might elicit negative responses from a section of the population because it would also have implications on brand endorsements. So, whenever anyone takes a stand like this, I’d like to believe it’s the athletes doing it themselves. They know they’re going to get trolled, but they’re okay with it.”

Unfortunately, these are rare instances in India. While globally, athletes are ambassadors of a lot of causes in the larger socio-economic fabric, you hardly get to see that in India. (Unless, of course, it’s a global movement like Black Lives Matter that does not directly affect Indians.) “Athletes should be able to say what they want. Unfortunately, we are living in an environment where that’s not always possible,” says the senior executive.

But in the rare instance where an agency has to deal with an athlete who is politically invested and wants to express their opinion, it’s important for both parties to align with what they stand for and how they want to be perceived, says Siddharth Raman, deputy CEO at sports-focused digital media agency Sportz Interactive.

“In the social media age, where everyone has an opinion, you know that you’re not going to be surrounded by yes-men only. There will be a section that comes after you. Are you willing to deal with the storm when it hits you? If you feel you can come out of that unscathed or with limited damage, I think it’s fine. But that conversation needs to be had with the agency upfront.”

Siddharth Raman, deputy CEO, Sportz Interactive

Meanwhile, Sehwag continues to refer to India as Bharat. Interestingly, he had no issues saying India until June this year. The mentions of India on his X timeline dried up starting July, which was when 26 political parties came together to form a new alliance called the Indian National Developmental Inclusive Alliance, with the backronym INDIA.

But, as Sehwag insists, his reasons weren’t political.

⚡️Quick Singles

⚽️🏆🌏 Saudi Arabia could have competition in its bid to host the 2034 Fifa World Cup. Reports suggest Australia and Indonesia have held talks to launch a joint bid, which could include Malaysia and Singapore too. Fifa, though, seems set on Saudi Arabia. The governing body even tweaked its rules around the number of established stadiums that a country should have to bid for a World Cup to accommodate Saudi Arabia.

🏅🏟️🇮🇳 Even as cricket is set to be included in the 2028 Olympics, International Olympic Committee chief Thomas Bach said he has noted India’s “great interest” in hosting the Games in the future. The corruption allegations around the 2010 Commonwealth Games in India would have no bearing on the decision, he added. There have been reports that India might bid to host the 2036 Olympics.

🐭🇮🇳💰 American private investment firm Blackstone is the latest party that has been linked with buying The Walt Disney Company’s India assets. Blackstone is exploring either buying a combination of assets, including sports properties and the Disney+ Hotstar streaming service, or the whole Disney India portfolio, reported The Economic Times. Other companies that reportedly held talks with Disney include Reliance Industries, Adani Group, and Sun TV.

If you enjoyed reading The Playbook, please share it with your friends, family, and colleagues. Please also subscribe to it (for free) if you haven’t already.

You can reach out to me at jaideep@thesignal.co with any feedback (good, bad, or ugly), tips, and ideas. I'd love to hear from you!

Thanks for reading, and see you again next Friday!