India’s baby steps towards becoming the world’s sports shoe factory

Global suppliers of top sportswear brands such as Nike, Adidas, and PUMA are setting up manufacturing units in India as they look for alternatives to China. Is the country ready for this shift?

Good evening,

Welcome to The Playbook, a weekly newsletter on the business of sports and gaming. If someone shared this newsletter with you or if you’ve found the online version, please hit the subscribe button below — it’s free! You can unsubscribe anytime.

Last weekend, I watched Air, the Ben Affleck-Matt Damon movie about how Nike pursued and eventually signed Michael Jordan when he was still a rookie. If you haven’t seen it yet, please do so first thing after you finish reading this newsletter. It’s super!

There’s a quote in the movie by Nike’s former director of marketing, Rob Strasser, played by Jason Bateman: “A shoe is just a shoe until someone steps into it.” I don’t want to give away any spoilers, but Jordan’s mother, played by the powerhouse Viola Davis, tweaks that quote brilliantly towards the end of the movie.

For the purposes of this week’s edition of The Playbook, I’d like to tweak the quote too, if I may. Ahem… a shoe is just a piece of rubber and plastic until someone makes it. #sorry

You might have noticed I didn’t mention leather. There’s a reason for that.

Why Nike, Adidas, PUMA, and Co. are making in India

Photo credit: Luis Villasmil/Unsplash

Do you have a pair of sneakers or sports shoes from a global brand like Nike, Adidas, PUMA, Decathlon, ASICS, etc. that cost less than ₹4,000 (~$50)? If you do, check the label. There’s a good chance they’re made in India.

India’s sports footwear industry is at a crossroads. There’s a lot happening, and the next few years could define the country’s stature in the global footwear market. In terms of the current size, India’s overall footwear industry is worth ₹82,000 crore ($10 billion), according to the Ministry of Commerce and Industry. Non-leather footwear accounts for 75% of it—that’s ₹61,500 crore ($7.4 billion). This includes all kinds of non-leather footwear, including flip-flops, sandals, and shoes.

And this figure could rise very soon.

In recent months, there have been reports that the top manufacturing partners of global non-leather footwear brands such as Nike, Adidas, PUMA, and Reebok are setting up units in India. In April, the Indian subsidiary of the world’s largest branded athletic and casual footwear manufacturer, Taiwan-based Pou Chen Corporation, signed an agreement with the Tamil Nadu government to set up a ₹2,302 crore (~$280 million) unit in the state.

At least six other Taiwanese majors are also in the process of setting up units in Tamil Nadu, reported Business Standard. These are Feng Tay, Hong Fu, Dean Shoes, Oasis Footwear, Sports Gear, and Zucca.

“...we are in talks with Taiwan Footwear Manufacturers Association to rope in at least 30-40 mid-size companies too, so that an entire ecosystem develops in Tamil Nadu.”

—V Vishnu, managing director and chief executive of Guidance Tamil Nadu, the state’s investment promotion agency, to Business Standard

The Pou Chen investment is expected to generate more than 20,000 jobs over 12 years. Earlier this month, Deccan Herald reported that Pou Chen, Feng Tay, and the Chennai-based Phoenix Kothari Footwear have pledged investments worth ₹6,000 crore ($727 million) for setting up non-leather footwear manufacturing units in Tamil Nadu, which will employ ~80,000 people. The ultimate aim is to attract investments worth ₹20,000 crore ($2.4 billion) in the sector by 2025, the report said.

Now, India has a fabled history of manufacturing leather footwear and goods. The country accounts for 13% of the world’s total leather production. States like Tamil Nadu are known to produce high-quality leather footwear for global luxury brands such as Louis Vuitton, Prada, and Ferragamo. India exported leather footwear worth over $2 billion in the year ended March 2022.

Photo credit: Engin Akyurt/Pexels

In comparison, India’s non-leather footwear exports in the same year were worth just $214 million. The country has never really been known as a hub for making non-leather or sports footwear. Why then are all these suppliers of the world’s top sportswear brands coming to India?

None of the Taiwanese companies responded to my request to participate in this story except Feng Tay, which declined to comment. Nike, Adidas, PUMA, and Decathlon also did not respond. I then spoke to several senior executives from India’s footwear and sportswear industries to understand what’s happening. Some of them requested anonymity because they’re either not authorised to speak with the media or wanted to protect business relationships. They told me there are multiple reasons behind this growing interest in India.

Primarily, what we’re seeing is the “China plus one” strategy at play. Western companies have been looking for backups to China to manufacture their products, for various reasons: rising labour costs in China, pressure from the Xi Jinping government to transfer technology to Chinese competitors, growing geopolitical tensions between the US and China, and stringent Covid lockdowns.

India is the only country with a labour force and market size comparable with China. Since coming to power in 2014, the Narendra Modi government has also introduced various initiatives to boost local manufacturing, such as production-linked incentive (PLI) schemes, free trade agreements, and easing foreign direct investment (FDI) rules. Just earlier this week, The Economic Times reported that the government is considering rolling out a PLI scheme for the footwear industry.

India has also sought to improve the ease of doing business in the country, and overhauled its customs rebates. As a result, companies from various industries—electronics, semiconductors, solar panels, wind turbines, toys, and footwear, to name a few—are making India their plus-one. India recorded its highest-ever FDI inflow of $84.8 billion in the year ended March 2022.

“India fits the bill pretty well because the government consciously doesn't allow a lot of Chinese investment in Indian companies,” says Dhirendra Lodha, director of sourcing and marketing at Fashinza, a tech platform that solves manufacturing for fashion brands. “Many Chinese companies have opened or acquired big manufacturing setups in countries like Indonesia, Cambodia, and Vietnam. So, if you go there, you’re still indirectly sourcing from China. In Vietnam, 40-45% of the investment is from Chinese companies. In Myanmar, it is 70-80%. So, India stands out in a big way.”

A footwear factory in Cambodia (Photo credit: Marcel Crozet/ILO/Creative Commons BY-NC-ND-2.0)

The Indian government has also been increasing import duties on footwear. “During my time, it was 10%; now, it is 35%,” says Rajiv Mehta, managing director of PUMA South Asia from 2005 to 2014. He’s currently the managing director and general partner at Athera Venture Partners, an early-stage venture fund. “Imported footwear has become more expensive. Indirectly, the government is saying ‘make in India’. It wants to promote local manufacturing of sports footwear, like in apparel, and wants it to have export potential, like leather footwear,” he adds.

Another reason why brands are moving manufacturing to India is the Indian consumer’s shift towards athleisure, especially since the pandemic. In December 2022, Mehta’s successor at PUMA, Abhishek Ganguly, told The Economic Times that “athleisure has become the go-to outfit” in India. “Nearly half of the Indian population is below 25 years old, and things such as fashion consciousness, per capita footwear consumption, and aspiration in tier-2 and tier-3 [cities] will only grow,” he said.

The shift towards athleisure caught the attention of not only the major global suppliers of the top sportswear brands, but also Indian leather footwear manufacturers. “Global luxury brands like Louis Vuitton and Gucci started making sneakers and athleisure even before the pandemic,” says Mehta. “As a result, the orders that Indian leather manufacturers were getting from these brands started declining. Now, the same manufacturers who make leather footwear for Louis Vuitton and Co. are taking orders from Decathlon for flip-flops and sports shoes.”

Photo credit: PxHere

A worker at a leather footwear factory can be trained to make non-leather footwear in six months, according to N Mohan, director and CEO of the footwear business at Kothari Industrial Corporation Limited (KICL), a Chennai-based conglomerate.

“Making non-leather footwear is a large-scale, volume-based, mechanised production, where you can make 50,000-100,000 pairs a day. In comparison, leather footwear employs a boutique manufacturing approach, with only 2,500-3000 pairs a day,” says Mohan, who was previously the CEO of Clarks India.

“This large-scale mindset is very well understood by the Taiwanese and Koreans because they created the industry around the world—in China, Vietnam, Indonesia, and Cambodia. Now, they’re looking at India as a consumption market and a manufacturing base,” he adds.

That’s not to say the Taiwanese manufacturers are new to India. The likes of Feng Tay and Apache Footwear, which are one of the main suppliers to Nike and Adidas, respectively, set up shop in the country in 2006. “Today, these two companies together export 50 million pairs of shoes from India,” says Mohan.

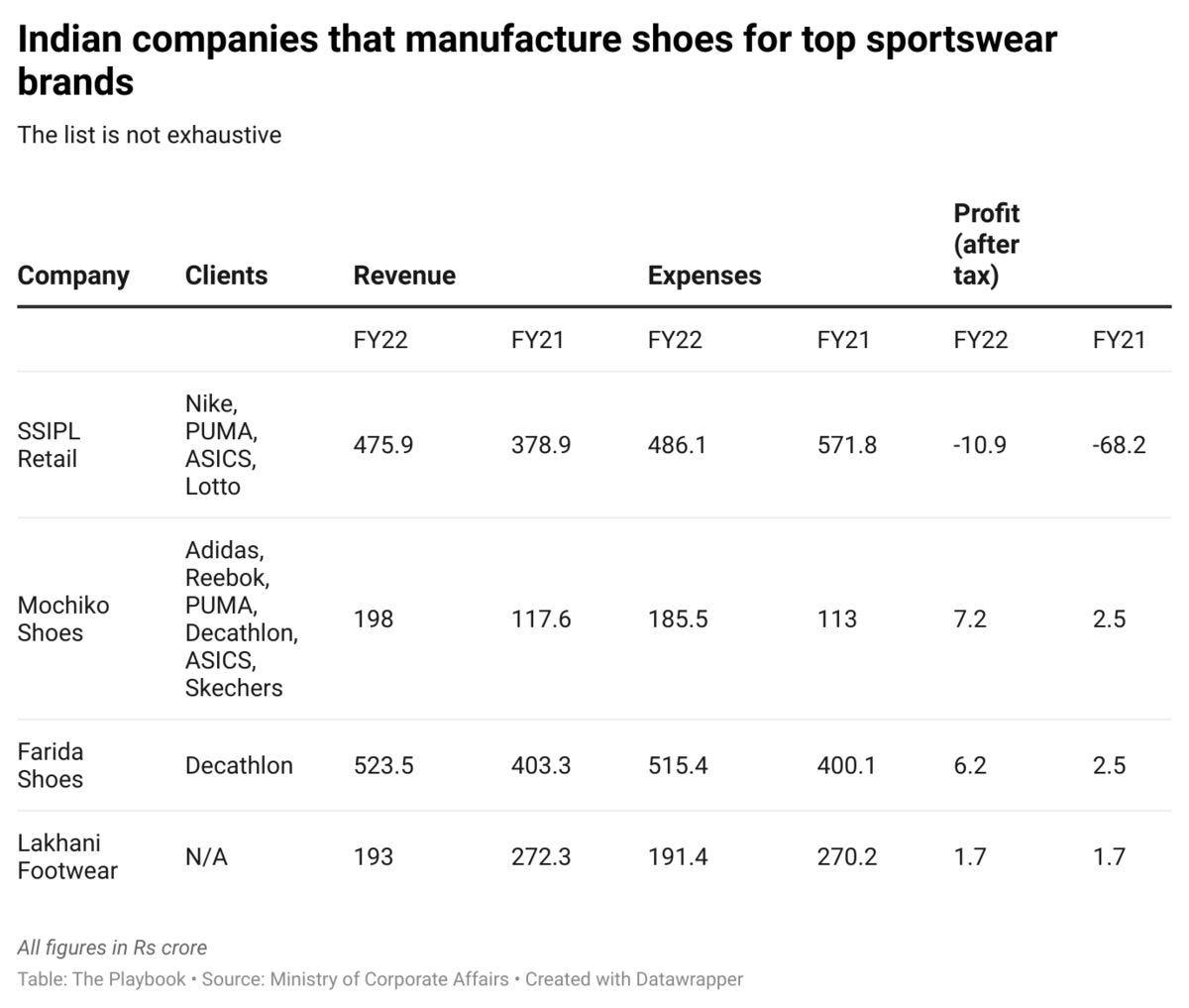

And it’s not just Taiwanese companies who make shoes for these top brands in India. New Delhi-based sportswear company SSIPL has been making shoes for Nike for over 20 years. It also manufactures footwear for PUMA, ASICS, and Lotto. According to its website, the company makes 2.4 million pairs of shoes a year. Other prominent Indian manufacturers for global sportswear brands include the Farida Group (Chennai), Mochiko Group (Dehradun), and Lakhani Footwear (Faridabad).

Looking at the success of the likes of SSIPL and Mochiko, many casual-wear brands like RedTape and US Polo started getting into sports footwear in the mid-to-late 2010s, says the senior footwear industry executive. “Meanwhile, international brands like Skechers took the lead in capturing the walking shoes segment, making the slip-on shoe a rage. Most of the domestic brands copied them left, right, and centre. This was when most of the brands were doing semi-knocked down or complete knocked down programmes.”

Then, as Covid struck and brands scampered to shift their manufacturing base from China, Indian manufacturers sniffed an opportunity and started beefing up their operations. “They imported the required machines, etc. and geared up to decrease the dependency on importing raw materials. Some of them did strategic tie-ups with top brands, which included either a long-term order commitment or mutually co-investing in the factory,” the senior footwear industry executive adds.

However, it’s one thing to create a manufacturing ecosystem in the country. Finding quality raw materials is the hard part.

India has the raw materials for the sub-₹3,999 segment, which are less design-focused and largely for the domestic market. The raw materials include polyurethane (PU), mesh, insole, midsole, outsole, laces, reinforcement, glue, and trims, which are all available in India.

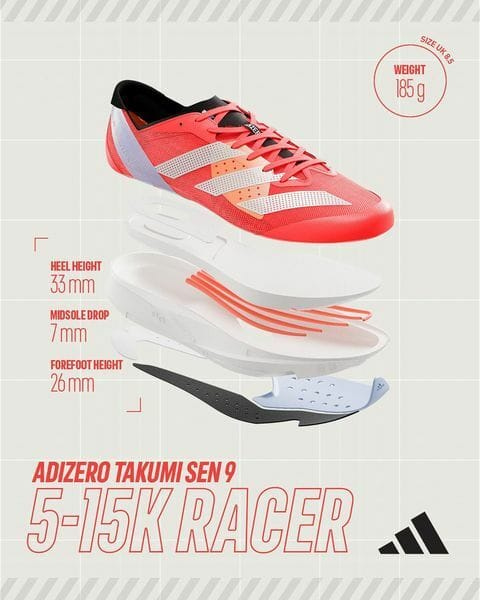

But above that price point, you need better-quality PU, ethylene vinyl acetate (EVA), and textiles. The shoes will have more foam and less rubber, so that they become lighter. The laces are lighter and more premium as well. These raw materials are more difficult to source in India. “We import the mould for the outsole, glue, EVA granules, and TPU (thermoplastic polyurethane) films,” says the senior footwear industry executive.

The Adizero Takumi Sen 9 full-length LIGHTSTRIKE PRO midsole is paired with glass fibre ENE...

Importing raw materials makes the end product expensive. With every imported component, you’re paying a duty of 18-30%. That’s where India is still far behind China, where footwear factories have built design and product development capabilities over decades. This is why any shoe from a top global brand priced above ₹5,000-6,000 ($60-70) is likely to be made in China.

As a senior official from a global sportswear brand says, “Brands would prefer working with a supplier who’s constantly doing research and development, and giving them solutions that will work for the next seven-eight years. It can be a very small thing like a differentiated mesh, or improving the PU’s performance by 10% every year or right up to the full design.”

In India, however, companies are content with duplicating what China is doing and building super-factories that assemble products, the official adds. “That helps in terms of giving employment to Indian labourers, but labour is just 8-9% of the product cost.” A second senior executive from a global sportswear brand says that when China gets new technology in its factories, “Indian manufacturers buy the old tech and call themselves high-tech companies.”

Having said that, Indian factories working with Taiwanese suppliers are getting many insights into the functioning of the sports shoe industry. The owners of the factories will start understanding the margin levels at which the industry works, while their workers imbibe the soft skills required. “And once the local supply of raw materials improves, these factories could start creating their own setups and getting direct POs (purchase orders) from the brands,” says Fashinza’s Lodha.

While the Taiwanese suppliers are largely assembling footwear in India, most Indian manufacturers make the shoes end-to-end. But that’s also because they’re making cheaper shoes and largely catering to the local market.

“In India, over 50% of footwear sold costs less than ₹500,” says KICL’s Mohan. “Another 30% is up to ₹1,000. Between ₹1,000 and ₹3,000 is 10%, while the remaining is for over ₹3,000. But slowly, the price acceptability is improving, thanks to the younger generation.”

Photo credit: PxHere

Most industry executives I spoke to say that Indian factories can make more expensive shoes, the ones priced above ₹3,999, but the availability of raw materials is limited. Vendors are unlikely to set up shop in a region where there isn’t sufficient demand.

“For manufacturing, you need certain volumes,” says Rishab Soni, chairman of SSIPL. “As you go higher up the price scale, the MOQs (minimum order quantities) decrease. You need a few thousand pairs per style to justify the entire manufacturing process. Brands are able to get those quantities in the entry and mid-segment pricing, so they rely on Indian manufacturing. Wherever they feel it’s challenging to get the MOQs, that’s when they rely on imports.”

As mentioned above, the Indian government is reportedly considering launching a separate scheme to boost local manufacturing of raw materials for the footwear industry. The government has also issued guidelines under a Quality Control Order (QCO) for footwear made from leather, rubber or polymers, which will be enforced from July 1. Once implemented, retailers will have to procure Bureau of Indian Standards (BIS)-compliant footwear from manufacturers.

Footwear retailers have sought more time to implement the norms since the existing infrastructure and testing facilities at most factories are not sufficient to cater to the stringent BIS certification requirements. They added that BIS has still not published product manuals for some standards, testing equipment, testing methodologies, and procedures.

Photo credit: Central Footwear Training Institute

What’s clear is that India is gearing up to join the big league of sports footwear manufacturing, but there are several hurdles on the route. The experts I spoke to all concurred that India should aim to become a true manufacturing alternative to China in the next three years and replace it within seven years.

Mehta from Athera Venture Partners says a lot will depend on the work ethics and attitude of Indian factory officials. “Indians will always try to find a jugaad, which ultimately reflects in the product quality. Are the owners of the factories on the shop floor ensuring that things are up to speed? Are people getting pulled up if shipments get delayed or rejected? Are you ensuring the stock for India consumption is not being compromised in terms of the quality of the packaging, etc.?”

If all goes to plan, in the next five to seven years, Indian factories should reach a stage where the workers won’t know whether they’re making a shoe for the Indian market or for export until it reaches the packaging stage. “That’s how it happens in China—they just know that they have make 10,000 pairs of the same shoe. Only then will we see a flywheel effect,” says Mehta.

KICL’s Mohan and SSIPL’s Soni are both bullish about the near future. Mohan expects India’s footwear consumption to grow from 2.6 billion pairs a year to 5.5 billion pairs in the next five years. That’s about four pairs per person per year. He also expects exports to increase to at least 600 million pairs a year in the next seven years, up from the current 60 million.

“India is what China was 20 years ago,” he says. “Once these international players set up shop here and create competition, the domestic industry will improve.” And with BIS coming into play, imports will be curtailed, which will help Indian manufacturing, says Soni.

If things go to plan, who knows, perhaps five to seven years from now, you’ll see a made-in-India Nike shoe worth ₹10,000.

If you have a made-in-India shoe from a top sportswear brand, how satisfied are you with the quality?

That’s all for this week. If you enjoyed reading The Playbook, please share it with your friends, family, and colleagues. Please also subscribe to it (for free) if you haven’t already.

You can reach out to me at jaideep@thesignal.co with any feedback (good, bad, or ugly), tips, and ideas. I'd love to hear from you!

Thanks for reading, and see you again next Friday!